The Imperial Sensorium - Part Two

A new essay by New Design Congress' Benjamin Royer on the violent world built in the 20th Century by the nuclear order and proponents of cybernetics.

A note from Cade: This is the conclusion of the essay written by Benjamin Royer, lead researcher at New Design Congress. Part One was published last Friday. It traced the birth of nuclear technoaesthetics in the shadow of the atomic bomb, the rise of cybernetics, and the enmeshing of the two disciplines as they shaped our world. The full essay + supporting images and references is available on our website.

Nearly two years of work between New Design Congress and our collaborators is crystallising into research documents, exhibitions, digital tools and policy interventions, and we’ll be sharing a lot in the second half of 2022. If you aren’t already, please consider supporting our work via a recurring subscription or one-time donation. Our broad range of support helps us to maintain critical independence.

“The fully enlightened earth radiates disaster triumphant”

“Everyone wants to know whether these technologies will work. As far as I'm concerned, they already work. We got the money.”

David Mizell, during the 1985 Conference on the Strategic Computer Initiative

“When I say this pocket camera is ready in a flash, I mean ready in a flash!”

Advertisement for the Kodak Ektralite 10 instant camera, 1986

The coupling of cybernetics with atomic science birthed entire industries of consumer goods. The building blocks of the nuclear technoaesthetics, which had served to capture the tests and its victims at ever increasing resolutions, started to flourish commercially. This took the shape of entire markets of consumer and professional goods: cameras, film, radar, medical equipment, radiology, media technologies, electronics, and of course computers.

Amped by the nuclear arms race, the “virtual arms race” soon followed. The novel model of research and development used in war, counter-insurgency and spycraft was embraced by the Free Market: demand was artificially created, and offer buoyed by massive public funding – a financial projection of imperial power that continues well into the 21st century. Throughout the 1950s, more than half of the funding of major US tech corporations – IBM, Bell, General Electric, Raytheon, etc. – came from various federal and state governments, DARPA, and an entire network of parasitic and publicly funded military wings. The 1960s saw the now cash-fat private sector invest heavily in research and development. IBM, who had furnished the Nazis with its intelligent business machines to bring efficiency and automation to the Holocaust, reinvested 50% of its profits in internal R&D. Thus came to existence the industrial titans of the newborn computer industry, founded through capital and knowledge derived from genocides and ecological annihilation.

The Cold War decades would in particular see the market for virtual representations blossom, synthesised in partnership with information technology titans. In every case, their existence was to fortify the immediate needs and desires of the nuclear-imperial order’s “closed world.” The Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), the first general-purpose digital computer, was built during WWII, but, late to the party, entered service only after the end of the conflict. Having missed its chance to compute actual destruction, the project’s first computations were directed towards calculating simulations for the hydrogen bomb.

Through projects like ENIAC, cybernetics ascended from its analogue limitations, reaching its full potential through digital computing. The new opportunities afforded by the partnership weren’t limited to fantasising world-ending weapon strikes, but also their sensuousness. One of these examples was Whirlwind, conceived originally as a general piloting simulator. Plagued with a chaotic development, Whirlwind nevertheless raised “dozens of possibilities, including military logistics planning, air traffic control, damage control, life insurance, missile testing and guidance, and early warning systems,” but more importantly “the whole idea of combat information and control with digital computers.”

It was the jingoistic mindset of the US Air Force (USAF) that found within this technology an ideal outlet. As military brass hallucinated Red invasions across the globe, Whirlwind was rescued, re-purposed and given a context a posteriori. Spliced with other technologies under the aegis of the Eisenhower-backed USAF, Whirlwind was given a new life as the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE), a centralised system of threat detection and defensive response led by digital computers. Much like the nuclear scientists separated from their underground tests, here the technologically-mediated representation of the world glowed on the screens of the command centre. SAGE was the harbinger of new evolutions in computer technology, such as networking, video displays, synchronous parallel logic, multiprocessing, modems and software diagnostic programs, which rapidly disseminated through the commercial sector and formed the foundation of modern computing. The US private sector developed its ability to manufacture large networked systems of real-time data-processing through SAGE. For all that, it also “barely worked.”

In October 28, 1962, a satellite was interpreted by the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) as a Soviet nuclear first strike launched over Georgia. The US bombers were readied to take off for an immediate counter-strike, only to be called off at the last minute. This was but one amongst the many similar events of brinkmanship caused by technical faults or the misidentification of weather and wildlife. Moments of planetary communication, computing and sense-making giving way to annihilation, stopped by the scepticism of human minds and the belatedness inherent to human bodies. Like the Odum brothers and their professional class, nuclear technoaesthetics and cybernetics had been mobilised to generate simulations of senses and information that conformed to the desires of its creators. The seeds of future virtual representation mismatches were planted. The errors plaguing the fully-automated Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) produced false-alerts from the start, and in some cases very nearly ended in full-scale nuclear ‘retaliations.’ The Worldwide Military Command and Control System (WWMCCS) exhibited a high message transmission failure rate. And the forlorn techno-fetishist pursuit of the “Star Wars” Strategic Defence Initiative (SDI), “an ideological fiction whose computer-controlled nuclear defences would not have worked and could not have been built,” continued to be financed well into the 1990’s.

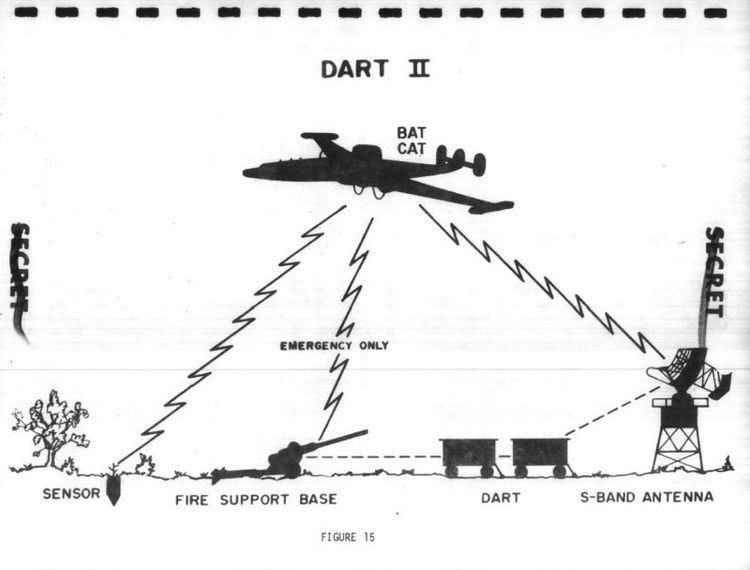

The offensive complement to the defensive strategy of SAGE, ‘Operation Igloo White’ generated in 1968 an idealised representation of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, one that manifested through sensors and aerials deployed in the jungle and the interfaces of the command and control room. The Vietnam War was the first war to employ a highly centralised, management-led military machine of pure quantification and computerisation. In the pursuit of this endeavour, Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara enlisted the help of the system-men, economists and social scientists of the RAND Corporation to economically manage the war effort in Vietnam. Developed from McNamara’s earlier experience at Ford Motors, the techniques of class warfare engineered in business schools found their natural progression in the prosecution of an imperialist war, seen from the start as “a kind of industrial competition.” Like the Odum Brothers’ Pacific experiments, Vietnam was seen by both McNamara and Walter Rostow (an influential advisor to both Presidents Kennedy and Johnson) as a “test case.” The country, its populations and landscapes were colonised as a laboratory for scientific and military purposes, the two industries complimenting each other and sharing the same discourse.

Despite the claims of its creators, Igloo White’s legacy was a world of fantasy rather than a supreme precognitive machine. Its automated missile strikes launched from patrolling F-14 – a configuration that foreshadowed drone warfare – often targeted empty patches of jungles, killing wildlife and scarring landscapes. Its sensors were easily fooled by fake noises and bags of urine from the guerrilla resistance. The operation killed scores of civilians and wildlife, created 13.000 refugees, and the loss of 300 to 400 US aircraft. Ultimately, Igloo White failed to stop the Ho Chi Minh Trail. It remained, officially, a success.

While informatised warfare foundered in the field, its proponents ultimately succeeded in the discourse. Yet new states of things weren’t created ex nihilo. Rather, the techniques they articulated became the relay points of tendencies decades in the making, catalysts for certain configurations of power to crystallise and sustain themselves. And while the military-men oversaw and funded their financing and deployment, it was the scientific cadre who defended their ‘less aggressive’ potentials – despite all evidence to the contrary. These simulations remained firmly plugged in to very real tests on populations, animals and landscapes, as well as the purposeful destruction of the environment, alimented by the dense network of capitalist exploitation.

This complemented a movement towards a US-centric sphere of economic control,1 where the rabid development of new potentials unleashed by new technologies gave the US private sector an important edge. Counter-insurgency and government-toppling kept cheap commodities flowing from the peripheries to the imperial centre. The technological and virtual arms race would only gain momentum during the Carter and Reagan administrations, between the increase of nuclear warheads per missiles, the restrictions imposed on academic research, and the development of ever more potent and far-reaching missile technologies. It was the Reagan administration that however thoroughly seized the techno-nuclear war-machine, and in their vision of an apocalyptic struggle suffused with Christian fundamentalism, only accomplished what engineer Vannevar Bush had already noted in 1945: war as “increasingly total war, in which the armed services must be supplemented by active participation of every element of the civilian population."

Bush’s vision was perfectly understood by the RAND Corporation who, in 1997, advocated publicly for “comprehensive approaches to conflict based on the centrality of information.” The technical innovations of “low-intensity” counter-insurgency warfare and other “operations-other-than-war” – enshrined by the likes of Frank Kitson with the massacre of the Mau-Mau and other colonial “peacekeeping” – would be helpfully completed by an understanding of the cyberwars and netwars soon to be waged in the virtually-mediated sphere.2 In this “increasingly total war” that refuses its name, the private control over information and the State nuclear war-machine, born from the same primordial soup, accomplished the totalising vision of the system-men: a true “End of History” where the “Last Man”3 could be guided to more amenable course of action by technoaesthetic prods.

Alphaville Dēlenda Est

In the field of representation what constitutes capital is visible identity and the power to command the desires of others.”

Jan Verwoert, You Make Me Mighty Real – On the Risk of Bearing Witness and the Art of Affective Labour in Tell Me What You Want You Really, Really Want

“We shall use the power of computers to undertake an editing process on behalf of the only editor who any longer counts – the client himself […]. If we can encode an individual’s interests and susceptibilities on the basis of feedback which he supplies, if we can converge on a model of the individual of higher variety than the model he has of himself, […] marketing people will come to use this technique to increase the relatively tiny response to a mailing shot which exists today to a response in the order of 90 percent […]. The conditioning loop exercised upon the individual will be closed. Then we have provided a perfect physiological system for the marketing of anything we like – not then just genuine knowledge, but perhaps ‘political truth’ or ‘the ineluctable necessity to act against the elected government.’ Here indeed is a serious threat to society.”

Stafford Beer, Managing Modern Complexity in The Management of Information and Knowledge

Radiation ecology had been one step towards the whitewashing of nuclear technoaesthetics. But the cooperation between the former and cybernetics could only achieve so much beyond the realm of clinical quantitative observation and digital machines. As Norbert Wiener emphatically hammered, it was “the purpose of Cybernetics to develop a language and techniques that [would] enable us to indeed attack the problems of control” of, among other things, human beings. This project implied seducing more people than simply a political-managerial class — and seducing them profoundly.

Apart from its macro-level efforts with social sciences, cybernetics had involved psychologists from the start, such as in key positions in the engineering of SAGE. The meta-discipline had convinced itself that its closed-loop, command-and-control vision of society would accomplish, as cybernetician Lawrence Frank put it, “the dynamics of social life aris[ing] from individual actions, re-actions and interactions […].” This implied “the study of individual personalities.” Cognitive psychology arose, influenced significantly by cybernetics, superseding behavioural psychology and its mechanistic framework whose mechanical reductionism saw individuals as trainable automatons. The new psychological vision was enthralled by this veneer of liberatory emancipation. Norbert Wiener himself pictured cybernetics as allowing the freeing of energies and communication within heterogeneous entities, an ecology of constant and dynamic analysis, exchange and interactions. This represented a powerful ethic geared towards the realisation of a qualitative jump beyond the quantitative perspective. It was to however calcify into an authoritarian ordering of a quantified world, making full use of the insidious discourse and configuration of power tied to the informing of the living: “the quantitative passe[d] into the qualitative, but only as represented.” 4

Over the years, theorists J. C. R. Licklider, Silvan Tomkins and others attempted to psychologically encode the informatisation of the world. Licklider was a psychologist and an early cybernetician – and someone who, as seen earlier, was not especially troubled by the danger of informational reductionism. Fascinated by the connection between psychology and computer technology, he shaped the early developments of network communication alongside AI and personal computing. Licklider was a veteran of SAGE who “aggressively promoted a vision of computerised military command and control,” and he envisioned a world where humans would be assisted by computers – “second sel[ves]” that would help the hapless organic beings reckon with the complexities of the new information age. An alluring sentiment that would find wide purchase, such as in Steve Jobs’ 1990 description of “the computer [as] the equivalent of a bicycle for our minds.” This “man-computer symbiosis” would, in the last analysis, be efficiently directed under the all-sensing gaze of automated and centralised decision processes.5

Tomkins was a psychologist and personality theorist, who sought to develop an understanding on how exactly “the automaton must be motivated.” Combining the cybernetic framework’s utilitarianism with a vulgar understanding of 17th century philosopher Spinoza’s ethics, Tomkins’ approach encoded the spinozist affects as organic feedback mechanisms, nine or so affect programs “genetically hard-wired […] each of which manifests itself in distinct physiological-autonomic and behavioural patterns of response.” Tomkins’ work would be embraced and extended by his student Paul Ekman. The latter ended up deeply fascinated by the bodies and expressions of Indigenous Balinese and Australians during their ritual practices, captured on ethnographic movies shot in the 1930’s. These observations, synthesised within Tomkins and Ekman’s theories, would inform the pseudo-science of micro-expression analysis, and lead Ekman to become “centrally involved in the creation of the Screening of Passengers by Observational Techniques (SPOT) program, funded by the Department of Homeland Security after 9/11,” which “employs Behavioural Detection Officers (BDOs) at airports for the purpose of detecting behavioural-based indicators of threats to aviation security.”

This new "ethico-technical economy of life,” a configuration of cybernetics and clinical gaze tinged by nuclear technoaesthetics, attempted the qualitative jump by weaponising a totalising comprehension of both mechanical and organic understandings of systems. Such approach, wherein, as seen earlier, the “living and nonliving could be intermeshed,” birthed a machinic conception of both quantification and desire. In this ecology of a “radio-active world,”6 the pressures of the act of governing, traditionally deployed on individual subjects, are replaced by an act of management on a system of relations. Within this new paradigm, the enmeshing of cybernetics and nuclear technoaesthetics reaches an apex, and “the inner workings of the animal, machine, or person need not be known; it is a ‘black box,’ known through a complete listing of its past behaviours.” The observed target is modulated through their environment in a way that sidesteps the traditional categories of subjectification and subjection. Instead, this approach embraces the technical projection of a constellation of profiles, identities, and the interactions connecting them – be they social media accounts, public service records, travelcard logs and, already, blockchain transactions.

Norms arise (seemingly organically) from the dense mesh of synthetic relations and the continuous informing of harvested mass of behaviours separated from their context of origin. With little to no real consent, this purposeful black box accomplishes the separation of subject from observation and materialises the value of the epistemological bounty. It is a natural progression of the biopolitics described by Michel Foucault, from which neoliberalism derives: an insidious affecting of the body and mind to produce and consume, to sense and move, obtained by “manipulating the variables of the environment.” No surprise that Friedrich Hayek, the Austrian economist and co-founder of the neoliberal project, observed how cybernetics echoed Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand. In helping economists understand the "self-organising systems” of the markets and their “steering mechanism”:

“[…] the model or representation can perform or predict the effects of different courses of action and pre-select amongst those results that which in the existing state is ‘desirable,’ it will also be capable of directing the organism to that course of action which has thus been ‘mapped out’ for it.”7

This departure from the parochial definitions of liberal philosophy8 can be intensely felt at the borders of States and the enforcements without and within. Powered by Palantir and its competitors, State programs like the US ICE dragnet, Australia’s Border Force and the European Frontex utterly defang ‘sanctuary’ or other refugee policies that still remain within the confines of this political tradition. In these situations especially, the term ‘biopolitics’ hides the necessary flip side of regulating life: objectifying and dehumanising its subjects in the pursuit of management. The governmentality of the centres was forged with the sowing of misery and death in the peripheries, be it under the shape of assassinations, genocides or irradiation of landscapes. Biopolitics necessarily implies thanatopolitics – both the literal extinction of life, but also the extinction of the power of life: the power to move and be moved.

At the heart of the management models of governance and counter-insurgency doctrine lies again the principle of data fusion, where cyberneticised information is the uni-form substance that subsumes every facet of life. Petrify and kill, terrorise and murder: a program nowadays applied through the aptly named Gorgon Stare (the wide-area surveillance sensor system equipped on Reaper drones) or the techno-bureaucratic apparatus geared towards breaking the Uyghurs’ spirit. All made possible via “a form or pattern of life that conforms with the paradigm of ‘information based on activity’” established “to spot the emergence of suspect elements based on their unusual behaviour.” But, as we can see from the absurdities of nuclear research and the error-prone cyberneticised systems of sensing, these are frequently “totally disconnected from their real effects on the ground.”

Yet therein lies precisely the cyberneticised act of governing: the deaths of individual targets are less important than the corrective action the assassination triggers on the system. This is an intervention, as anthropologist Talal Asad makes clear, whose "primary aim is not the protection of life as such but the construction and encouragement of specific kinds of human subjects and the outlawing of all others.” The proponents of this revolting logic rightly perceive the lives they extinguish less as individual foci of liberal governmentality, and more as another cybernetic flux to be managed. Terrified by the brittleness of their “vulnerable world,” some among these advocates now fancy themselves fantasising a “high-tech panopticon” where “[e]verybody is fitted with a ‘freedom tag,’” monitored by a “freedom officer [who] can also dispatch an inspector, a police rapid response unit, or a drone to investigate further.” Anything that could prolong the existence of their murderous civilisation, where “some net totalitarianism-risk-increasing effect […] might be worth accepting.”9

“Yet man will never be perfect until he learns to create and destroy; he does know how to destroy, and that is half the battle,” said the Count of Monte Cristo. “Technocracy alone offers life” would have shot back Howard Scott, the founder of the 1930s Technocracy movement. As the post-WWII nuclear technoaesthetics solidified into an ecology through their cybernetisation, the protagonists attempted to reconcile the vile roots of this syncretic enterprise. An enterprise which, despite its repeated abject failures, delusions of grandeur and disconnect from reality, nevertheless constantly failed upward. For within the coils deployed by this ethical world-building of cosmological proportion, we are to this day ensnared precisely as we are spurred.

Of Cosmic Forks

“Because it implies accountability, knowing and showing together constitute an epistemic practice to which ethics and politics become available, even necessary.”

Lisa Gitelman, Paper knowledge, toward a history of documents

“[W]e will all have to become what Simondon calls ‘technical poets.’”

Adam Nash, Affect, People and Digital Social Network

The ramifications of nuclear technoaesthetics form the very backbone of our infrastructure. Every region has been choked by the Free Market and its techno-scientist apparatus. What is the alternative? To dismantle the primacy of cyberneticised information is to dismantle its self-anointment as the conduit for actions and thoughts. It is to resist both the associated discourse that only empowers the hierarchies imposed by an imperial centre, and the representational schemes based on the epistemological claims of data. Dismantling cyberneticisation is to decide between closing, foreclosing or forking the negative commons that we inherit and upon which much of our industrial society rests. What connects us to the negative commons we’ve ended up with? Who relies on them for work, for survival? How do they generate and hold information, social communion, or expression? What are their pathways for revenue, rent or speculation?

Like subaltern studies scholars have already explored, philosopher Yuk Hui suggests considering the notion of fragmentation. This process necessarily originates from the epistemological practices of the embodied localities and the first concerned, constituted in epistemic communities. Such formations are, for instance, “the communities who had been displaced by the weapons tests and then prematurely resettled in an irradiated landscape” and who “began to mobilize their own embodied sensory practices as well as testimony about the sensory violence of the nuclear testing regime.” It therefore accomplishes the dual task of tactically exploiting every window of opportunity created by the mismatches residing within the incumbent powers’ representations and modes of sensing; all the while discarding our reliance on technologies stemming from their hegemonic epistemology that might have seduced us.

Yet we should be careful not to fall for the trappings of a ‘local’ or a ‘decentralisation’ that perfectly fits the project of atomised neoliberal firms at every level – be it individual, familial, associative, governmental and supragovernmental. Neither should we resume the local to the sclerosed geographical or cultural enclaves fantasised by nationalism. How could this be accomplished? Focus could for instance be directed towards the concrete project of descaralisation, the purposeful and programmatic reduction, where needed, of the scale of the production sphere and the logistical chains. Following Jasper Bernes, interrogating negative commons through fragmentation is “to graph the flows and linkages around us in ways that comprehend their brittleness as well as the most effective ways they might be blocked as part of the conduct of particular struggles.” In this “process of inventory, taking stock of things we encounter in our immediate environs, that does not imagine mastery from the standpoint of the global totality, but rather a process of bricolage from the standpoint of partisan fractions who know they will have to fight from particular, embattled locations,” we can “produc[e] the knowledge which the experience of past struggles has already demanded and which future struggles will likely find helpful.” Vitally, this will also redirect resources towards targeted communities by compensating, in money and in kind, their active involvement, building up on the already existing economic solidarity models of these communities and online subcultures.

The claim to intelligibility generated by the coupling of cyberneticised information and nuclear technoaesthetics is dysfunctional, sociopathic and brittle. The real always spills over the fences constructed by its representations. It isn’t the substance-information presented with pseudo-objectivity that leads our desire, but the myriad combinations of the ways we're affected. The forms arising from the hegemonic epistemological process are but one way, and recycling them over and over through a closed-loop system can only engender a stale understanding of the world. Refusing this despotic hold over existence is an aspect found in all critiques of power, from the Luddites to Decolonialism. Such refusals are the antidote to these planetary-scale systems and global governance structures rebranded as saviours of crisis, but whose core is the same illegitimate power that mistakes geese for missiles and brutalises life and land alike. By dismantling the world of cybernetics and nuclear technoaesthetics, by embracing, instead of denying, the flotsam and jetsam that irrigate individuations, becomings and political imagination, we might yet thwart this pretence of control over the real, the virtual, and all forms of life.

Benjamin Royer

Spring 2022

Edited by Cade Diehm.

Thanks to moss heim and Howard Melnyczuk for their feedback.

The full essay + supporting images and references is available on our website.

If you aren’t already, please consider supporting our work via a recurring subscription or one-time donation. Our broad range of support from individuals, organisations, companies and other entities helps us to maintain critical independence.

Initiated by Eisenhower, despite his teary-eyed 1961 Farewell Address targeting the “military-industrial complex” he himself contributed to create.

Where cyberwar describes a command and control approach to information warfare, netwar is the guerilla equivalent.

To paraphrase Francis Fukuyama and his vulgar reinterpretation of Alexandre Kojève.

Alèssi Dell'Umbria, Antimatrix.

Whose shape can also be decentralised and distributed. It doesn’t affect the centralised nature of the control exerted. Peter W. Singer cites for instance the case of a four-star general micromanaging in real-time a drone operator in Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century.

As Nigel Thrift put it, with an aspirational tone entranced by nuclear technoaesthetics, in From Born to Made.

Friedrich Hayek, quoted in Paul Lewis, Purposeful behaviour, Expectations, and the Mirage of Social Justice: The Influence of Cybernetics on the Thought of F. A. Hayek. As Paul Lewis recalls, one of Hayek’s earliest work, the Sensory Order, published in 1952, was a psychological treaty borrowing many concepts from cybernetics.

Which still relies on liberal concepts for many of its assumptions. Antoinette Rouvroy and Thomas Berns note this conceptual tension in Algorithmic Governmentality and Prospects of Emancipation, whereby “algorithmic governance further entrenches the liberal ideal of an apparent disappearance of the very project of governance” while eschewing or ‘avoiding confrontation’ with many liberal concepts.

Nick Bostrom, The Vulnerable World Hypothesis.