The Imperial Sensorium - Part One

A new essay by New Design Congress' Benjamin Royer on the violent world built in the 20th Century by the nuclear order and proponents of cybernetics.

A note from Cade: This is Part One of a two-part essay by our lead researcher Benjamin Royer. On a personal note, this is an important text as it identifies the shortcomings of the systems that govern the world and informs the interventions we undertake at New Design Congress. Part Two will be published early next week, and the full essay + supporting images and references will be available on our website at the same time.

Nearly two years of work between New Design Congress and our collaborators is crystallising into research documents, exhibitions, digital tools and policy interventions, and we’ll be sharing a lot in the second half of 2022. If you aren’t already, please consider supporting our work via a recurring subscription or one-time donation. Our broad range of support helps us to maintain critical independence.

“Providing a veil for profit-making is not the most interesting dimension of the logic of capitalism. What matters more is the way in which private companies can extend their authority over the social order.”

Mirca Madianou, Technocolonialism: Digital Innovation and Data Practices in the Humanitarian Response to Refugee Crises

The colonial order casts a looming shadow over our modern times. If capitalist powers were in large part responsible for this subjugation of people, landscapes and resources through military, economic and political means, there were many other actors for whom the economic gains represented only secondary importance. To appeal to a techno-scientific class driven by world-building narratives rather than profit motives or strict martial discipline, the engineering of this global order was framed by the social politic of the day, from the rallying cry of World War II, the purge of communist anti-colonial partisans or the promise of a post-industrial middle class utopia.

This difference in motivation, carried by the rhetoric of civilisation and enlightenment, enabled colonialism to rely on a cadre of scientists, researchers and engineers projected by the State military, in order to weave systems of domination through industrialisation and, later, informatisation. Complex sets of representation, designed to map the acquisition of resources and the exploitation of labour, were enshrined. They remain operational to this day.

Yet the contradictions between the colonialist forays of the scientific community and the economic incentives of Capital direct much of our methods of sensing and informing. These contradictions confuse our attempts at reckoning with this inheritance. How have the digital and technological realisations of colonialist desires seized our senses? How can we parse the technological developments of the nuclear-imperial order and its influence on the concepts of information and knowledge? To come to grips with how people are moved1 requires a study of what shaped the desires of the technocracy, for it very well might shape ours. Such an inquiry implies disentangling the convergence of aesthetics and cybernetics. Seeking to discern the sensible essence of things, aesthetics aims at discovering these forms that affect human existence.2 Cybernetics geared itself towards making the chaotic world intelligible and organisable into observable systems. How has their interfacing altered, widened and narrowed our ability to comprehend, govern and act?

As we face a global collection of crises, almost all symptoms of imperialist brinkmanship, we must understand the influence of the cyberneticisation of thought that underpins not just our economic models, but our abilities to understand how contemporary power structures thrive in enforcing powerlessness by mortifying the living. Grasping at straws, aghast at the enormity of the dangers already unfolding before us, we turn in desperation towards the same solutions – and the same classes of people – that caused these problems to begin with.

The Eternal Sunshine of the Atomic Mind

“The instituted knowledge of society, as it exists in recorded history, is the knowledge obtained by the dominant classes in their exercise of power. The dominated, by virtue of their very powerlessness, have no means of recording their knowledge within those instituted processes, except as an object of the exercise of power.”

Partha Chaterjee, The Nation and its Fragments

“By demonstrating that they would not recoil from a civilian holocaust, the Americans triggered in the minds of the enemy that information explosion which Einstein,3 towards the end of his life, thought to be as formidable as the atomic blast itself.”

Paul Virilio, Strategy of Deception

“You think that typhoons are shocking? Wait till a man is out to have his fun!”

Bertolt Brecht

In 1945, the Manhattan Project successfully split the atom, testing first in the New Mexico desert and twice more on densely populated Japanese cities. In little more that three horrifying weeks, the nuclear explosion had materialised from a mathematical theory into an unfathomably deadly practice.

The atomic bomb was an engineering-driven project of heretofore unseen magnitude4 that propelled nation States into the irreversible imbalance of Mutually Assured Destruction (M.A.D.) diplomacy. The Western psyche withered in the shadow of the mushroom cloud, accelerating a psychological and ethical hostility towards the living world and its inhabitants. This was by no means a new development. Centuries of thoughts and colonial practices had already enshrined a deep animosity, laced with fantasies of control, against the natural world. The conceptual hodgepodge that came to define ‘Nature’ within the Western mind appears in retrospect less like a well-reasoned concept, and more like the embodiment of every facet of the Other – and a discursive mechanism fashioned to exploit them.

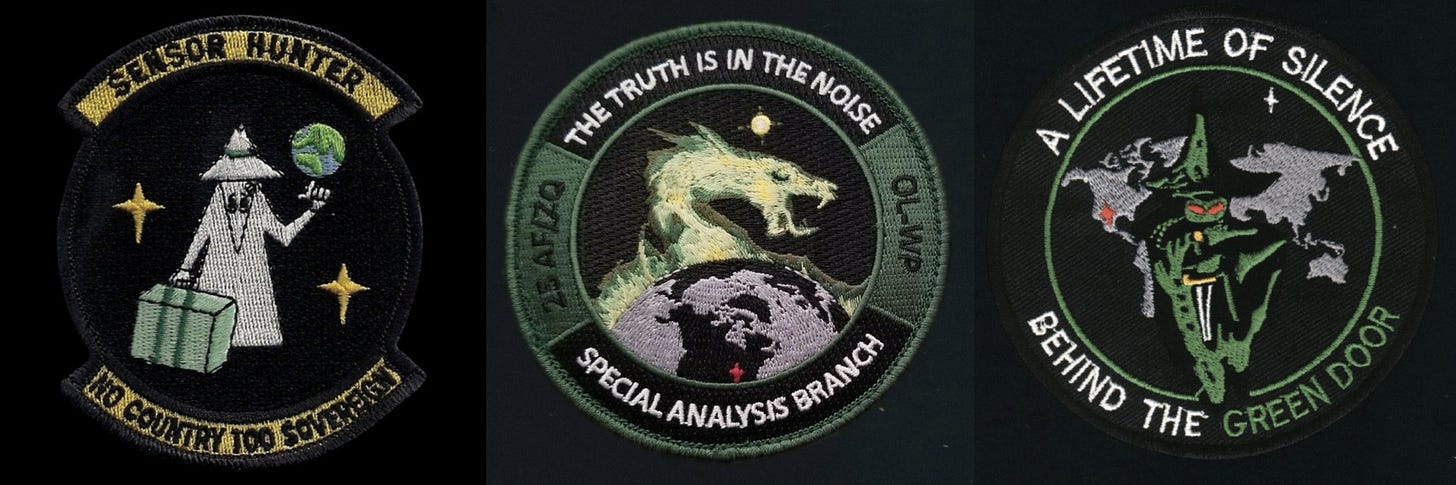

Institutionalised through the political and technological reconfigurations that arose from WWII, the Cold War and decolonisation, this obsessive lens to read the world became suffused with nuclear technoaesthetics. Defined by Joseph Masco and further developed by John Shiga, nuclear technoaesthetics describes the evaluative aesthetic categories embedded in the expert practices of weapons scientists, the systematic approach directing the sensing and the making sense of the new topology of the world. Its colonialist goals remained unchanged, now complemented by “legal discourse which presented discriminatory, exploitative, and violent sensory techniques as necessary for the production of scientific knowledge.” The Pacific Islands for the United States, the Sahara for France, Australia for the United Kingdom, Kazakhstan for the USSR, Xinjiang for China: regions where imperial formations had scarred the Indigenous body and psyche were all earmarked for the testing of nuclear weapons.

In a grotesque mirror-image of nature, the mushroom cloud birthed a world-spanning mycelium, its tendrils captivating the techno-scientific class. The official and personal records of the US nuclear scientists display their attempts at grappling with the awe-inducing and highly taboo destructive power of their unanticipated success. The early nuclear period is full of images conjured by the scientists who took part in the overground tests, many sharing characteristics of religious awe rather than any understanding of the annihilation of people, animals and habitats. Rationalising these experiences required the development of ‘objective’ and ‘neutral’ representations to serve as epistemological foundations: sensor readings, documentary photographs, reporting – the systematised generation of technoaesthetic artefacts geared towards the cultivation of a clinical gaze. The increasing existential, physical and intellectual separation experienced by the scientific teams underpinned this epistemological process. In overriding sensory experiences through discourse and technique, entire fields of science saw their dual abilities to sense and react captured. In place of a revulsion for questionable or violent research, a false sense of intellectual control arose, which formed the aesthetic experience of the nuclear apocalypse into one that was pleasurable, even desirable. These discursive and technical mechanisms accomplished a threefold purpose: measuring the success of nuclear tests, (re)producing configurations of power, and dulling the monstrosity of this ‘advancement of knowledge.’

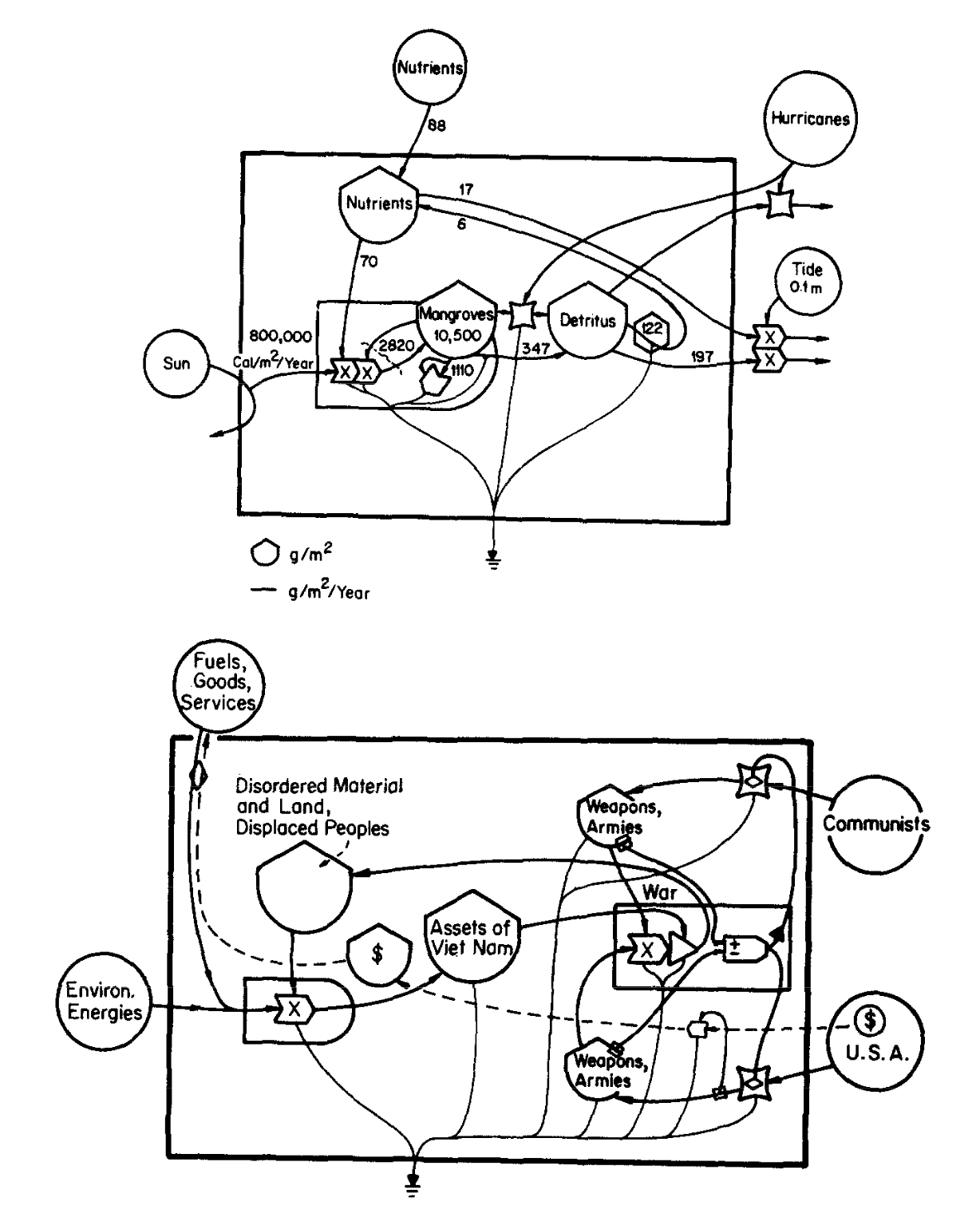

In the Western-occupied Pacific Islands, biologists Eugene and Tom Odum eagerly harvested data from irradiated life and landscapes. In June 1954, the brothers departed for the Enewetak Atoll, excited to study what they called “entire ecological systems in the field” on the Pacific Proving Ground. They were determined to make the facts fit their theory: revealing the ecosystemic form at the heart of the environment. Their fieldwork was marred with frustrating hurdles, inconsistencies and mistakes. Stumbling with colonialist incompetence every step of the way, they exploited the deadly irradiation caused by ten nuclear weapons in order to show evidence of symbiosis, which they documented in an article for Ecological Monographs in 1955. Depicting Enewetak as “little affected by nuclear explosions,” this article would become a stepping stone for their careers, and Eugene Odum went on to publish his Fundamentals of Ecology in 1959, a tremendously influential book which dedicates a chapter to the new discipline of radiation ecology – the epistemological exploitation of nuclear fallout.

To facilitate this exploitation, the Atoll was labelled “primitive” and “secluded.” The informational forays of the scientists accomplished a civilisational role, making the islands “alive like a university campus.” Nothing could obviously be further from the truth. The Pacific Islands, far from a fantasised primitive form to begin with, had in any case been thoroughly seized by the Invisible Nuclear Hand, and their beaches were littered with industrial debris and military equipment. This discursive strategy wasn’t just geared towards the estrangement of the colonised, but an important prerequisite for the epistemological harvest: studies and analyses could only be adequately performed on an idealised ‘virgin body,’ with conditions artificially re-contextualised as comparable to the sterile and controlled environment of the laboratory.

A new banality of evil5 was unleashed by the progressive reliance on pure technological mediation. Even before the 1963 Atmospheric Test Ban Treaty, scientists privileged the data collection of their improvised technical sensing devices over the direct experience of irradiated communities. These were testimonies of “blisters in their mouths from the [irradiated] food,” the visual confirmation of “the effects of radiation in the trees and plants they ate from,” or the horror at the sight and sound of Geiger counters manned by male scientists publicly scanning the naked bodies of Indigenous women. The Atmospheric Test Ban Treaty itself was born less from a concern for public health (the irradiation of the US population following the 1955 Apple II device test) than strategic interest (countering foreign intelligence). It cemented the focus away from the reality of the manufacture of the bomb to the technologically-mediated physics of its detonation. The quantifiable perspective soon took over, under the form of pure mathematical and virtual mastery – and fever-dream fantasy. In cinemas, the "Body Snatchers" of 1956 projected an ever-present ideological invasion threatening US territory, just as the RAND Corporation assisted the Atomic Energy Commission during ‘Project Sunshine’ in the harvest of thousands of corpses, body parts and organs without consent. In the skies, radar sightings of flying swans became bombers in attack formation.

This shift towards computerisation thoroughly affected the scientific perception of the environment. The purpose of the living world and its inhabitants was to “ensure ‘optimal’ outcomes for the deployment of nuclear weapons and the tracking of their effects.” Data, considered a strategic asset ripe for exchange and exploitation, were not only directly captured from the bodies of the colonised populations and territories, but very much injected, under the form of presupposed taxonomy made intelligible for the colonial gaze. This brutal in-forming, performed at gunpoint and realised technically, manifested the epistemological bounties arising from mechanisms of power designed to dominate, extract, hierarchise and subdue. Conversely, entities that refused their dissolution inside this blinkered model were labelled “inhomogeneities,” a denomination that presupposed their eventual homogenisation within nuclear technoaesthetics, and their mobilisation as a resource for the exercise of power.

The experiences of the 20th century scientific community was the symptom of a broader disorientation of Western societies following the atrocities and entrenchment of fascism, the devastation of WWII, and the slow entropy affecting the colonial order. The reality of the atomic bomb – a cornerstone of technical fetishism and colonial dominance – thus became the hinge point from which deteriorating systems of power attempted to rejuvenate and redeploy themselves. The discursive mechanisms they employed to support that end, derived from systematised modes of sensing, became a cardinal way of viewing and informing the world, one that complemented rising industrial enterprises and technologies of communication.

Do Cyberneticians Dream of Electronic Revolutions?

“In communication engineering we regard information perhaps a little differently than some of the rest of you do. In particular, we are not at all interested in semantics or the meaning implications of information.”

Claude E. Shannon, The Redundancy of English

“Ether, having once failed as a concept is being reinvented. Information is the ultimate mediational ether. Light doesn't travel through space: it is information that travels through information... at a heavy price.”

Donna Haraway, The High Cost of Information in Post-World War II Evolutionary Biology: Ergonomics, Semiotics, and the Sociobiology of Communication Systems

As the Odum brothers were busy proving themselves in the Pacific, scientists at the Oak Ridge Laboratory in Tennessee were also struggling to interpret their fieldwork due to the overflowing intricacy of natural interactions triggered by their irradiation of the environment. By 1958, the researchers turned to computers as a solution: designing models that would simulate the complexities of radiation and its deployment through land and life. The burden of interpretation lifted quickly, and their mathematical models institutionalised closed-loop system virtuality over empirical predictions. The complex demands inherent in documenting the deadly practice of irradiating life and landscape was perfectly complemented by the rise of cybernetics, engendering the field of system ecology.

Eugene Odum had by 1963 risen to chairman of the Ecological Society of America’s International Biological Program committee, and had become a major proponent of cybernetics. This was the natural continuation of nuclear technoaesthetics, the sensing and informing framework to artificially model the interaction of a natural milieu. The perspective of combining these fields split Western ecologists, but eventually established itself as the dominant theory. In a paper written in 1981 with Bernard Patten, Odum presupposed the existence of a secondary informational network regulating nature, asserting that:

“Analogy, and the willingness to accept it, are the keys to identifying the cybernetic machinery of the ecosystem. To achieve orderliness (in nature), a secondary informational network is superimposed upon the primary one which regulated the conservative processes. Without such a network, nature would be chaotic, disorderly, and imbalanced.”6

This claim to intelligibility made possible by the informational approach was the particularly seductive aspect of cybernetics, a new ‘meta-discipline’ fashioned after the technologies of communication of the unfolding post-war era. It showed promise in bridging “the white spaces on the map of science” by seeking to “generate a new kind of link between engineering, biology, mathematics on one hand and psychology, psychiatry, and all the social sciences on the other,” and was eagerly adopted by leading figures of the post-war social sciences such as Gregory Bateson, Margaret Mead, John von Neumann and Talcott Parsons. Cybernetics devised axioms for the treatment of information, encouraged its proponents to refine communication technologies, even suggested that the framework could be employed to sense and quell social unrest.7

But whereas the bomb was an offensive technology, cybernetics was initially defensive. Its first application was to provide anti-air batteries the ability to track German airships, by continuously reinjecting in the weapon system the gap between the airships’ predicted and actual position. In this “logic consciously and dramatically materialised in the wartime technology of antiaircraft missile guidance […] freedom from holocaust and other social upheavals might be achieved through the construction of an all-encompassing system of feedback,” where informational pressures would be exerted on the system itself, relentlessly closing the gap between the actual situation and a desired result. As Peter Taylor further notes in his review of the technocratic optimism of ecology and cybernetics: “the individual in a feedback system appeared to gain in autonomy because systems theory addressed communication and information flow between individuals,” yet “communication systems were also command-control systems; command-control engineers would be required to ensure that the systems operated according to new criteria – for example, minimising information loss or preserving circuit stability.” Moreover:

“In the systems view, living and nonliving feedback systems alike obeyed common mechanical principles, including their mode of evolution. Data could be used to elucidate directly the dynamics of systems. And, once scientists understood the dynamics of systems, those systems would be controllable […]. The new theorists of feedback systems conceived of nature as a machine and, at the same time, acknowledged the purposive and regulatory character of that nature-machine […]. Furthermore, the same terms could be applied to all systems, whatever their components; living and nonliving could be intermeshed, eliminating the separateness of biological relations from physical factors.”

Cybernetics therefore embraced a principle of information fusion, capable of codifying every facet of life – money, needs, power, health, intelligence, or even fitness – into data. By myopically focusing on the relation between an emitter and a receiver, cybernetics attempted to represent the whole of existence inside the homogeneous, self-regulating form of a system. Information became the quantifiable substance of reality, under the guise of statistically predictable signal and noise. The transcripts of the Macy Conferences, the meetings of the cybernetician minds held between 1941 and 1960, highlight the tension within this conceptual dichotomy:

STROUD: ...it is rather dangerous at times to generalize. If we at any time relax our awareness of the way in which we originally defined the signal, we thereby automatically call all of the remainder of the received message the “not” signal and noise. This has many practical applications.

LICKLIDER: It is probably dangerous to use this theory of information in fields for which it was not designed, but I think the danger will not keep people from using it. […] Nevertheless, the elementary parts of the theory appear to be very useful. I say it may be dangerous to use them, but I don’t think the danger will scare us off.

Its proponents were painfully aware of these heterogeneities that wouldn’t quite fit their insular model. These noisy and entropic discrepancies could nonetheless be seen as a reservoir of untapped opportunities – recall the previously encountered category of “inhomogeneities.”

The limitations of cybernetics were therefore significant, and shaped the broader process of cyberneticisation. Radiation ecology deployed its epistemological power through the release of isotopes in the environment and the tremors caused by the explosions of the nuclear tests: purposeful irradiation and destruction delineated the topological boundaries of the studied system, and assessed the environment’s resilience. The test and feedback cycle reified the interconnected totality of an ecosystem that could be formed around the desire of the nuclear-imperial order: sustain nuclear tests and wars indefinitely. The tensions between cyberneticisation and the world generated an endless frontier to be techno-scientifically administered, revised and expanded. This provided equally defensive and offensive strategies to make the real con-form relentlessly with desired projections.

Driven by academic and economic incentives, the cybernetic framework helped the perceived ‘soft’ science of ecology to gain a foothold in the political, scientific and public consciousness. The influence of this work was as far reaching as it was seductive. Cybernetics tinged ecological studies, seizing Western politics and policy. In the US, this new discipline made it all the way to the top. In summer 1967, the congressional hearings of the Subcommittee on Science, Research and Development of the US House of Representatives had politicians swooned by the prospect of managing nature.

Through cybernetics, the techno-scientific class construed radiation ecology as a peaceful use of atomic energies for managerial purposes. A broad vision pictured nature as a system in a state of rapid decay due to industrial pollution, carefully side-stepping the blatant issue of economic exploitation. A technologically planning to prevent disaster was enshrined. By the mid-1960s, cybernetics and the system-men had thoroughly seized the political imagination of the US public and private sectors. It remains somewhat ironic that their focus on informational systems blinded them so utterly from recognising systems of power, especially the one arising directly from their analyses. Yet in hindsight it strikes as painfully clear that this was desired, two complementing aspects of the same discursive process that accompanies deployments of power, as the latter faced increasing dissent from both inside and outside.

The conclusion to The Imperial Sensorium will be published early next week, and the full essay + supporting images and references will be available on our website at the same time. If you aren’t already, please consider supporting our work via a recurring subscription or one-time donation. Our broad range of support helps us to maintain critical independence.

Throughout this piece, ‘move’ will be employed in its dual meaning: physically and emotionally.

‘Form’ here does not possess its vernacular meaning of ‘shape.’ A form is the perceivable ‘essence’ of a thing. Form and matter constitute substance in hylomorphism. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guatarri see form as part of a complex assemblage together with substance, content and expression. Evidently, the numerous philosophical inquiries surrounding and determining the essence of things have profound political implications.

“Technology has also shortened distances and created new and extraordinarily effective means of destruction which, in the hands of nations claiming unrestricted freedom of action, become threats to the security and very survival of mankind […]. Here too we are in the midst of a struggle whose issue will decide the fate of all of us. Means of communication […] when combined with modern weapons, have made it possible to place body and soul under bondage to a central authority – and here is a third source of danger to mankind. Modern tyrannies and their destructive effects show plainly how far we are from exploiting these achievements organizationally for the benefit of mankind.” Albert Einstein, Out of my later years.

Nuclear research was the most heavily funded facet of the war machine, both due to the organisational effort necessary for the management arising from the new configuration of State-led research and development during WWII, and in terms of investment. The Manhattan Project spent more that $800 million in 1945, $100 million more than the Army and Navy combined. Paul Edwards, The Closed World.

To paraphrase Hannah Arendt.

Cited in Chunglin Kwa, Representations of Nature Mediating Between Ecology and Science Policy: The Case of the International Biological Programme.

Norbert Wiener's title for his seminal book on cybernetics was, after all, “the Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine". See also Peter J. Taylor, Technocratic Optimism, H. T. Odum, and the Partial Transformation of Ecological Metaphor after World War II.

I find it very interesting that an essay about the funding of the MIC and nuclear weapons and colonial wars (which continue to this day) does not mention anything about the private banking cartel that literally owns the US government and all vassal western countries that are the poodles of Washington DC.

The Federal Reserve is the single greatest source of inequality in the world. the Cantillion Effect crushes societies.

https://mattstoller.substack.com/p/the-cantillon-effect-why-wall-street

https://mises.org/wire/what-derek-carrs-contract-teaches-us-about-wall-street-and-income-inequality